A Different Kind of Nothing

The thing that most people don’t seem to understand about Donald Trump is that he has no ideology. He isn’t a conservative, his Republican values are superficial placeholders so that he can continue to claim the title, and more importantly the money that comes with Republican fundraising. His affinity for Christianity is tactical and his aversion to immigration has more to do, I think, with how it will go over with the people who elected him to office than his own views or ideals.

And yet, the more I say it, the more I can’t help but to think: Wait a minute. i’ve just described a version of my own espoused beliefs.

I regularly lament strict political ideological ties as personally restricting and structurally damaging, its use beyond organization and raising funds spilling over into needless purity tests and cross factional fighting that abandons the point of politics, to make the structure of people’s lives better generally. But if this was the case, does that make me just as bad as Donald Trump? has everything I’ve ever complained about him ultimately contributed to my own beliefs? Does the feckless nihilism I buy into about meaning and the material universe align with that of a conservative hedonist, advocating for a blind consumption of the world and its resources while my species burns itself alive and oppresses half its own people?

But this nothingness, or perhaps what I’d encourage people to do with it politically, does not exist in Donald Trump’s politics. At least, I’m hoping I can prove that now.

The ideological void within Donald Trump is not necessarily enlightened or in search of some form of transcendental truth that exists beyond the limiting restrictions of ideology. Instead, it’s more of a give-and-take, a quid pro quo of publicly vying for ideological values in favor for that ideology’s organized support. In many ways, it mirrors the soulless trade-offs of Trump’s deep, pervasive ties with organized crime as a businessman.

From the construction of the titular Trump Tower in New York City, to Trump’s mentor and legal confidant being the most infamous mobster defender in court, Trump’s whole life has been surrounded by organized crime, and the tactics its shares with these more intellectual forms of abuse and oppression. But I think it is this exact influence that forms the empty shell of his politics today.

Some of us who criticize the President have made this distinction many times. He runs the Republican party like the mob. He is their mob boss, who they must pledge an undying loyalty too. He rewards those who honor him and get his jobs done, while he persecutes those who attack him, aiming for their lives. Perhaps the accusations of “cult” and “fascist” are too far. Perhaps not. Perhaps they share an underlying symmetry with the real center of the Trump political schema: the mafia.

Trump’s politics is distinctly transactional and performative. It asks for something and only when it receives its wish will it deliver back what it has promised to you, or some form of it. Or no form of it, really. Because like organized crime, it’s not exactly built on trust. The mafia’s idea of trust and comradery exists within a framework of fear and intimidation. It might pretend to have values, but more or less, the mob’s values are to the family in charge. Trump’s takeover of the GOP has been in this exact image. His family, more or less, are the helm of the new party. His son, Barron, is treated as an heir to the Presidency, like a king, yes, but also like a mob boss. At this point, the distinctions that tie Trump’s politics to the mafia are so clear, so undeniable, that the 34 felonies don’t really matter anymore. Of course he has felonies. But at least he shook off doing any time. His underlings will take care of that.

This is nothing like the kind of politics I myself have espoused time and again. My rejection of the clear labels of political ideology don’t exist for what gain they give me. Though, I did once consider that. As a freshman at the George Washington University, not being in with either the campus Republicans or campus Democrats meant not really getting that exposure or connections the way I wanted. Time and time again, my peers often told me in our conversations they too felt the stinging uncertainty of the world corrode the certainty of their party affiliations, but that they stuck with it symbolically.

And this is an important distinction. America’s party’s, whether they be two or whether they be two hundred, can be and were once predominately seen as largely structural organizations. They were not just classes of ideological teams, but systemic structures that existed in the daily life of America, beyond elections alone, organizing, fundraising, campaigning and democratic organizing. Beyond viral moments or abstract battles over freedom and tyranny, they actually applied their respective philosophies to their lives, according to Johns Hopkins and Colgate University Political Scientists Daniel Schlozman and Sam Rosenfeld.

Today that daily structural politicking is lost in a confusing paradox that has since made political parties feckless and empty. Their symbolic purpose contains multitudes of ideological contours within the broader liberal and conservative labels, which themselves are a messy array of incomplete and fuzzy ideals and values, but viably they serve no more a purpose than to get people who agree with them to vote for the people they like and raise money for that purpose.

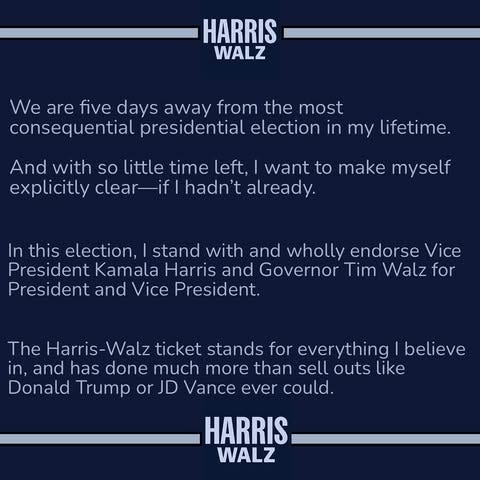

Reflecting on that many times, I often wonder if I should give in, then, and align with the party that most reflects me. During the 2024 election I endorsed Kamala Harris on that ground: that while I was not a Democrat on paper, her party contained the coalition I best liked. And yet, let’s say when I considered running for office after attaining my degree, an Independent run would be personally costly and deeply unpopular, unless the stars aligned perfectly for me. Moreover, the stifling demands of contemporary political ideology, crammed into the infantile guise of “the right side” of history would put me in a perceived moral minority. I would exist, more or less, as a boogeyman that disrespected the simple moral rules of contemporary American political life.

But, if I were to register as a Democrat, all I would ever hear in the back of my head is “you’re lying.” Not because the majority of my values don’t seem to often align with the structural schematic of Democratic party politics, but because the label itself and the unspoken (and spoken) rules of the Democratic party label wouldn’t be good enough for me. Good enough in the sense that there would be those times when I become a party defector, no doubt, rubbing against the grain of the party’s “official” stances on their direction, the country, and the universe. There would be something deeply superficial stuck to my politics as a Democrat, as there was when I claimed to be a Republican. Something that would keep me stuck here on earth, in the “real” world made of its myths and fantasies, while the universe and its existential dread and awesomeness waited for me.

In a way, the emptiness of my own political world and that of the President’s intersect. We both inhabit a space that exists outside of conventional party politics, we both often look past whatever the rules of politics are towards something more concrete and material. Where we diverge, I think, is at intent.

Trump’s intent is purely personal, it is obsessed with glory and fame and righteousness. It validates his existence and it funds his daily life, whatever that looks like. His family, his friends, his allies will all be taken care of however he sees fit at the end of the day. When I reflect on my own politics, I see a different kind of nothing. It is still nothing in that it sees the limitations on contemporary politics as not going far enough, never seeing wide enough. But rather than introspect, it looks outward. What I want personally is very different from a Muslim immigrant who lives in New York City, or a black communist living in Sacramento, California, or a White conservative from rural Oklahoma. And yet, of course, we’re all still human. Maybe none of us have “the” answer to the secrets of the universe, or the local rezoning ordinance or the affordability crisis. But maybe there is some material base line that we all ultimately want that can be shared, in some sense.

More importantly to me, maybe the effects of some actions aren’t nearly as bad or as good as we ever think they are. Maybe not all transactions are a zero sum trade off of what I want for what you want. Maybe that thing I think I want that I’ll lose if you get what you want never mattered. Maybe it was never real. The challenge, for me, isn’t just getting to the bottom of that dilemma, but searching inward, determining how that material resource or experience speaks to me, and flourishes that freedom, the only thing that actually exists in that nothingness, for me to explore and create in.